Ìwà ọmọlúàì

Etiquette ( /ˈɛtikɛt,_ʔkᵻt/) is the set of norms of personal behaviour in polite society, usually occurring in the form of an ethical code of the expected and accepted social behaviours that accord with the conventions and norms observed and practised by a society, a social class, or a social group. In modern English usage, the French word Àdàkọ:Wikt-lang (label and tag) dates from the year 1750.[2]

Politeness[àtúnṣe | àtúnṣe àmìọ̀rọ̀]

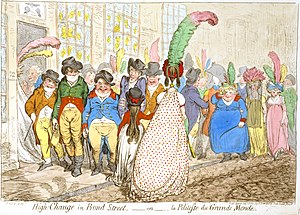

In the 18th century, during the Age of Enlightenment, the adoption of etiquette was a self-conscious process for acquiring the conventions of politeness and the normative behaviours (charm, manners, demeanour) which symbolically identified the person as a genteel member of the upper class. To identify with the social élite, the upwardly mobile middle class and the bourgeoisie adopted the behaviours and the artistic preferences of the upper class. To that end, socially ambitious people of the middle classes occupied themselves with learning, knowing, and practising the rules of social etiquette, such as the arts of elegant dress and gracious conversation, when to show emotion, and courtesy with and towards women.[3]

In the early 18th century, Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, wrote influential essays that defined politeness as the art of being pleasing in company; and discussed the function and nature of politeness in the social discourse of a commercial society:

Periodicals, such as The Spectator, a daily publication founded in 1711 by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, regularly advised their readers on the etiquette required of a gentleman, a man of good and courteous conduct; their stated editorial goal was "to enliven morality with wit, and to temper wit with morality… to bring philosophy out of the closets and libraries, schools and colleges, to dwell in clubs and assemblies, at tea-tables and coffeehouses"; to which end, the editors published articles written by educated authors, which provided topics for civil conversation, and advice on the requisite manners for carrying a polite conversation, and for managing social interactions.[4]

Conceptually allied to etiquette is the notion of civility (social interaction characterised by sober and reasoned debate) which for socially ambitious men and women also became an important personal quality to possess for social advancement.[5] In the event, gentlemen's clubs, such as Harrington's Rota Club, published an in-house etiquette that codified the civility expected of the members. Besides The Spectator, other periodicals sought to infuse politeness into English coffeehouse conversation, the editors of The Tatler were explicit that their purpose was the reformation of English manners and morals; to those ends, etiquette was presented as the virtue of morality and a code of behaviour.[6]

In the mid-18th century, the first, modern English usage of etiquette (the conventional rules of personal behaviour in polite society) was by Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, in the book Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman (1774),[7] a correspondence of more than 400 letters written from 1737 until the death of his son, in 1768; most of the letters were instructive, concerning varied subjects that a worldly gentleman should know.[8] The letters were first published in 1774, by Eugenia Stanhope, the widow of the diplomat Philip Stanhope, Chesterfield's bastard son. Throughout the correspondence, Chesterfield endeavoured to decouple the matter of social manners from conventional morality, with perceptive observations that pragmatically argue to Philip that mastery of etiquette was an important means for social advancement, for a man such as he. Chesterfield's elegant, literary style of writing epitomised the emotional restraint characteristic of polite social intercourse in 18th-century society:

In the 19th century, Victorian era (1837–1901) etiquette developed into a complicated system of codified behaviours, which governed the range of manners in society—from the proper language, style, and method for writing letters, to correctly using cutlery at table, and to the minute regulation of social relations and personal interactions between men and women and among the social classes.[9]

Manners[àtúnṣe | àtúnṣe àmìọ̀rọ̀]

Sociological perspectives[àtúnṣe | àtúnṣe àmìọ̀rọ̀]

In a society, manners are described as either good manners or as bad manners to indicate whether a person's behaviour is acceptable to the cultural group. As such, manners enable ultrasociality and are integral to the functioning of the social norms and conventions that are informally enforced through self-regulation. The perspectives of sociology indicate that manners are a means for people to display their social status, and a means of demarcating, observing, and maintaining the boundaries of social identity and of social class.[10]

In The Civilizing Process (1939), sociologist Norbert Elias said that manners arose as a product of group living, and persist as a way of maintaining social order. Manners proliferated during the Renaissance in response to the development of the 'absolute state'—the progression from small-group living to large-group living characterised by the centralized power of the State. The rituals and manners associated with the royal court of England during that period were closely bound to a person's social status. Manners demonstrate a person's position within a social network, and a person's manners are a means of negotiation from that social position.[11]

From the perspective of public health, in The Healthy Citizen (1996), Alana R. Petersen and Deborah Lupton said that manners assisted the diminishment of the social boundaries that existed between the public sphere and the private sphere of a person's life, and so gave rise to "a highly reflective self, a self who monitors his or her behavior with due regard for others with whom he or she interacts, socially"; and that "the public behavior of individuals came to signify their social standing; a means of presenting the self and of evaluating others, and thus the control of the outward self was vital."[12]

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu applied the concept of habitus to define the societal functions of manners. The habitus is the set of mental attitudes, personal habits, and skills that a person possesses—his or her dispositions of character that are neither self-determined, nor pre-determined by the external environment, but which are produced and reproduced by social interactions—and are "inculcated through experience and explicit teaching", yet tend to function at the subconscious level.[13] Manners are likely to be a central part of the dispositions that guide a person's ability to decide upon socially-compliant behaviours.[14]

Àwọn ìtọ́kasí

- ↑ Wright; Evans (1851). Historical and Descriptive Account of the Caricatures of James Gillray. p. 473. OCLC 59510372.

- ↑ Brown, Lesley, ed (1993). "Etiquette". The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. p. 858.

- ↑ Klein, Lawrence E. (1994). Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness: Moral Discourse and Cultural Politics in Early Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521418065. https://books.google.com/books?id=H6u6QyCKE5YC.

- ↑ "First Edition of The Spectator". Information Britain. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ Cowan, Brian William (2005). The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-300-10666-1.

- ↑ Mackie, Erin Skye (1998). "Introduction: Cultural and Historical Background". In Mackie, Erin Skye. The Commerce of Everyday Life: Selections from The Tatler and The Spectator. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 1. ISBN 0-312-16371-1. https://archive.org/details/commerceofeveryd0000unse/page/1/mode/1up.

- ↑ Henry Hitchings (2013). Sorry! The English and Their Manners. Hachette UK. https://www.google.co.uk/search?hl=de&tbo=p&tbm=bks&q=isbn:1848546661. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ↑ Mayo, Christopher (25 February 2007). "Letters to His Son". The Literary Encyclopedia. https://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=21002. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ↑ Rose, Tudor (1999–2010). "Victorian Society". AboutBritain.com. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ↑ Richerson; Boyd (1997). "The Evolution of Human Ultra Sociality". Ideology, Warfare, and Indoctrinability. http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/anthro/faculty/boyd/ultra.pdf.

- ↑ Elias, Norbert (1994). The Civilizing Process. Oxford Blackwell Publishers.

- ↑ Petersen, A.; Lupton, D. (1996). "The Healthy Citizen". The New Public Health – Discourses, Knowledges, Strategies. London: Sage. ISBN 9780761954040. https://books.google.com/books?id=RofiHHQddx0C. Àdàkọ:ISBN?

- ↑ Jenkins, R. (2002). Pierre Bourdieu. Key Sociologists. Cornwall: Routledge. ISBN 9780415285278. https://books.google.com/books?id=aPVaHgUx1f0C.

- ↑ Bourdieu, Pierre (1977). Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9780511812507.